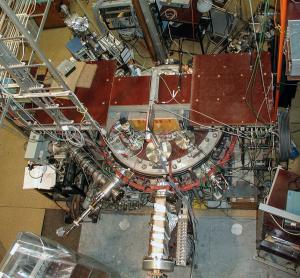

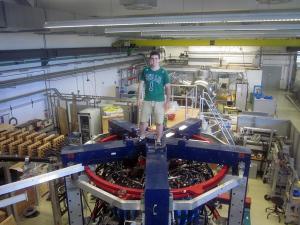

Canada entered fusion research in the late 1970s, and by 1986 the Canadian Centre for Fusion Magnetics (CCFM) operated an experimental tokamak in the Varennes suburb of Montreal. This medium-sized machine, named Tokamak de Varennes, specialized in the study of plasma-wall interactions, and for more than one decade formed the kernel of CCFM activity.

Unfortunately, by 1997 the project had to be folded for lack of funding. CCFM was left with a perfectly operational machine on its hands, potentially worth millions of dollars, and it was

ready to sell. Among the potential buyers was Iran, whose ambitious fusion research program had to rely on outdated machines.

The Iranian offer was in the range of USD 50 to 90 million (depending on the sources). It would have been enthusiastically accepted if the diplomatic context had been different: Iran was at the time under US-imposed sanctions and even in Canadian government circles, there was reluctance to realize the transaction.

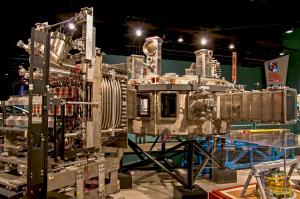

The solution to the dilemma came from General Atomics: in order to upgrade its DIII-D tokamak, the company needed powerful gyrotrons ... of the kind, precisely, that equipped the Tokamak de Varennes.

Amputating one of the heating systems from the machine considerably reduced its operational value and, as expected, Iran pulled out of the deal.