"The achievement of first plasma in Wendelstein 7-X marks an important milestone in the development of fusion energy: the device is the world's largest advanced stellarator and opens a new era in research into magnetically confined fusion plasmas," said David Campbell, head of the Science & Operations Division at ITER. "Its design is based on a sophisticated optimization of the magnetic field geometry which is predicted to allow the full exploitation of the potential of the stellarator configuration for fusion plasma confinement. Although smaller than ITER and not designed for operation with deuterium-tritium plasmas, the detailed studies of fusion plasma performance and physics processes to which the Wendelstein research program opens the gateway will be significant for the future development of fusion energy."

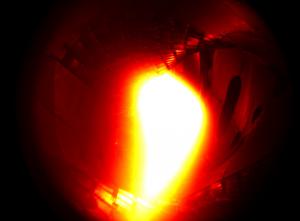

The operating team in the control room started up the magnetic field, initiated the computer-operated control system, fed approximately one milligram of helium gas into the evacuated plasma vessel, and switched on the microwave heating for a short 1.8 megawatt pulse. The machine's first plasma, which could be observed by the installed cameras and measuring devices, lasted one tenth of a second and achieved a temperature of around one million degrees.

"We're starting with a plasma produced from the noble gas helium," explained project leader Thomas Klinger. "We're not changing over to the actual investigation object, a hydrogen plasma, until next year. This is because it's easier to achieve the plasma state with helium."

"We're very satisfied," added Hans-Stephan Bosch, whose division is responsible for the operation of the device. "Everything went according to plan."

The next task will be to extend the duration of the plasma discharges and to investigate the best method of producing and heating helium plasmas using microwaves. After a break for New Year, confinement studies will continue in January, which will prepare the way for producing the first plasma from hydrogen.