Of tokamaks, hummingbirds and pizza ovens

A common but oversimplistic way of describing fusion is claiming that it's all about reproducing the nuclear reactions that occur in the core of the Sun. In a presentation to non-specialists on 18 January, ITER Director-General Pietro Barabaschi explained why, supposing we could mimic what happens in the Sun, such an undertaking would be totally "useless." The reasons he gave, and the images, parallels and comparisons he used, are what made his presentation particularly illuminating and enjoyable.

In terms of "volumetric power density," a key concept when dealing with energy issues, the Sun and Sun-like stars are very poor, very slow, and very inefficient systems. One cubic metre of the Sun's core generates about as much power as the chemical reactions inside an equivalent volume of manure—something in the range of 250 to 300 watts per cubic metre (W/m³), or much less than a human body (1 kW/m³). Hummingbirds, which hold the record of power density among living organisms, generate 50 kW/m³—that is, 200 times the performance of the proton-proton reactions inside the Sun. However, poor performance as a fusion reactor combined with giant size (333,000 Earth masses) is what makes the Sun what it is: a giant furnace that has been dispensing light and heat to for 4.6 billion years and will continue for another 5 billion years.

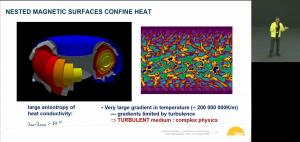

Provided one finds pertinent images and analogies, fusion on Earth can be relatively easily explained to non-specialists (with the notable exception of a few quantum phenomena, which according to the ITER Director-General "no one really understands"). Take the probability of deuterium fusing with tritium in a fusion machine, measured against that of hydrogen nuclei in a proton-proton chain. If the probability was a section (and in fact it is, it's called the cross section) deuterium-tritium's section would be comparable to that of the Moon and proton-proton the size of a virus. Energy confinement time, one of the biggest challenges in tokamak physics? Like adding blanket on a cold winter night in order to preserve body heat. (Except that there is no turbulence in bed covers, whereas there is quite a lot in fusion plasmas ... and that's a big issue.)

Then, there is the analogy of the wood-fired pizza oven which, like a tokamak cannot be too small (otherwise confinement is too weak and wood ignition will not occur) or too large (or else the surface power density would be excessive and lead to a carbonized pizza effect). Finding the right balance between size and power density is another considerable challenge that fusion R&D is facing and partly explains, from the ITER Director-General's perspective, why "fusion is taking so long."

Equations, plots and graphs were not absent from the hour-long presentation. Combined with paradoxes and amusing illustrations, it brought home to everyone present, both in the ITER amphitheatre and by remote connection, the most essential notion about fusion: not mimicking the Sun but tackling daunting issues which, helped by the progress of computer modelling in the coming decades, will make it an industrial reality.

Click here to view the recording of the presentation.