Michael Roberts: "We had a common objective to make fusion a reality"

Michael Roberts has a more than 40-year history with the United States fusion program, including over 26 years as Director, ITER and International Division, within the Fusion Energy Sciences (Office of Science) in the US Department of Energy (DOE). Since his retirement from the DOE in 2006, Roberts has continued to serve the US and international fusion community as Chair of the ITER Council Working Group on Export Control, Non-Proliferation and Peaceful Uses.

Could you situate the Geneva Summit in international fusion history?

Could you describe how the negotiation was prepared by advisors on both sides?

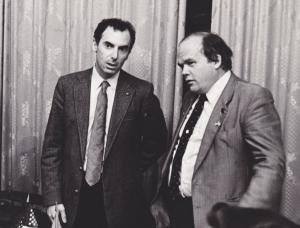

The negotiation leading up to the Geneva Summit was completed in secret. I was in a conversation in Moscow in late September 1985 where Evgeny talked to me about the idea. "Great!," I said. "But I can't make it happen on the US side." To his great credit, Evgeny realized that he had to pursue another way with Gorbachev. A little later, presumably after the Soviet side had given notice to the US side that this idea would be raised at the Summit, Alvin Trivelpiece, Director of the Office of Energy Research, and Secretary of State George Schultz worked in secret to prepare the US delegation to respond to Gorbachev's idea. It was news to us when Reagan said the words about working together in fusion in his television address to the nation right after the conclusion of the Geneva Summit!

Looking back, what do you see as some of your most important contributions to ITER?

I think ITER required the grease of people like me to make its complex mechanism go. People above don't have the time; people below don't have the freedom. There was a layer of people around the world: the Contact Persons for international fusion collaboration. We could work toward consensus or raise issues to higher levels. Everyone in the system knew me and they knew that I acted straightforwardly. We always understood that we could agree on the essence of what needed to be done. It's really personal—governments don't do these things, people do them. It's been a privilege to know all of these people and to be there when it happened.

What do you think other international science collaborations can learn from ITER?

I hope future project developers don't get scared off by the difficulties, but are intrigued by how to do it better. The cost for collaborative scientific projects continues to rise. We have to find a way to go beyond frustration and figure out how to work together. I'd like people to understand how much works about this project. ITER came out of an investment in one-to-one, face-to-face, person-to-person interactions. This developed trust and understanding that allowed us to pursue this collaboration.

There was a great deal of effort put into finding ways to accommodate every party's point of view on critical topics such as intellectual property rights, staff regulations, dispute resolution mechanisms, export control, and management audits. My recent experience with the ITER Council Working Group on Export Control, Non-Proliferation and Peaceful Uses offers another example of what works. All these topics, in fact nearly all the Articles in the ITER Agreement, deal principally with the practical aspects of collaboration at government level and not with the technical aspects of fusion, so these hard-won understandings among these major world parties could well be used for future projects in many fields of endeavor. We don't need to conclude "it's too complex." No one has to start from scratch again.

Michael Roberts began his career in fusion in 1966 at Oak Ridge National Laboratory after completing his Ph.D. in electrical (plasma) engineering at Cornell University. In 1979, he joined the DOE Fusion Energy Sciences and took on an international role representing the US at a staff level in international fusion collaborations. In 1994, President George H. W. Bush awarded Roberts a Meritorious Executive medal for his work in enabling the start of the ITER Engineering Design Activities. Throughout the formative years of ITER project development, Roberts was the US Contact Person for ITER and the lead US staff person for the many bilateral and multilateral collaborative fusion activities that underpinned the ITER activities. In 2007, President George W. Bush awarded Roberts a second Meritorious Executive medal for his work in enabling the successful conclusion of the negotiations for the ITER Agreement.