When fusion was (almost) there

Fifty years ago, in 1964, human beings believed in progress. Manned space capsules were routinely sent into space, a revolutionary supersonic commercial airliner was nearing the prototype stage, the computer mouse had just been invented, and the official decision had been taken to build a cross-Channel tunnel.

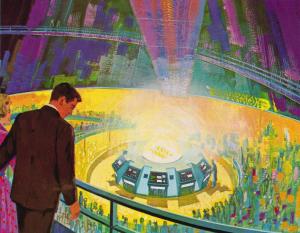

Nothing epitomized this optimistic and conquering mood more than the 1964 New York World's Fair. From 22 April 1964 to 17 October 1965, the World's Fair drew over 51 million visitors—more than the entire population of France at the time.

The huge exhibition showcased and exalted the promises of mid-twentieth century technologies. In General Electric's Progressland pavilion the public pressed around a rather strange machine—a quartz tube surrounded by magnets that gave off a vivid flash and a loud report at regular intervals: the Nuclear Fusion Demonstration.

Here's how it was described in the New York World's Fair official guide: "In the first demonstration of controlled thermonuclear fusion to be witnessed by a large general audience, a magnetic field squeezes a plasma of deuterium gas for a few millionths of a second at a temperature of 20 million degrees Fahrenheit. There is a vivid flash and a loud report as atoms collide, creating free energy (evidenced on instruments)."

The Fusion Demonstration left many visitors convinced that fusion-generated electricity was at hand, which of course did not reflect the actual state of fusion research. As General Electric reviewed its corporate involvement in fusion one year later, it concluded that "the likelihood of an economically successful fusion electricity station being developed in the foreseeable future is small."

Fifty years have passed. Since Progressland's quartz tube and the confinement of a 20-million-degree plasma for a few millionths of a second, progress has been remarkable. Beyond ITER, beyond DEMO (see the article on page 2), the "economically successful fusion electricity station" is programmed for the middle of the century. A prospect that is hardly more distant than the "foreseeable future" of 1965.