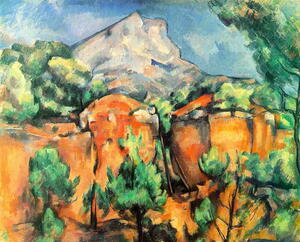

Rome's "Sainte Victoire" against the Barbarians

One of the most famous mountains in the world, along with Mount Fuji in Japan and Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, rises a few kilometres east of Aix-en-Provence. History gave it its name and art—its universal renown.

Long before Cézanne and other painters began celebrating the changing colours and form of the Mount Sainte-Victoire, a fierce battle had been fought here. The year was 102 B.C. Barbarian tribes from the North—everything that was not Roman then was considered "barbarian"—threatened the garrison village of Aquae Sextiae, the present-day Aix-en-Provence. The fall of this small stronghold founded twenty years earlier would mean that the road to Rome was open to Barbarian invasion. The threat was serious enough for Rome to dispatch to Provence Caïus Marius, one of its most brilliant generals and future consul.

Marius' army met the Cimbrian and Teuton barbarian tribes on a plain at the foot of the limestone mountain east of Aquae Sextiae. It was a terrible battle which claimed tens of thousands of lives according to Roman historian Plutarch—a bit of an exaggeration maybe. But there were so many corpses left on the battlefield that the plain was later referred to as "campi putridi"(the rotten fields). The name of a nearby village Pourrières—"pourri" is French for "rotten"—probably has its origin here. As for the limestone mountain, it was soon to be known as "Victoire," later Christianized to "Sainte-Victoire."

But as often happens, these etymologies are disputed. Frederic Mistral, the great 19th century Provençal author and poet, thought "Pourrières" stemmed from the word "porri," which is provençal for leek — a rather less glorious origin. As for the name Sainte-Victoire, it could well be related to Sainte Venture, to whom a chapel was dedicated in the 13th century, or more simply to Vintur, the Celtic God of high places who also lent his name to Mont Ventoux.

So much for history. Next in Newsline, we'll tell you about pre-history and how the region of Sainte-Victoire, not even a mountain yet, was home to large populations of dinosaurs. The dinosaurs are long gone, but the eggs they laid are still there—fragments of their shells literally covering the ground in some areas of the massif.