Melting tungsten for a good cause

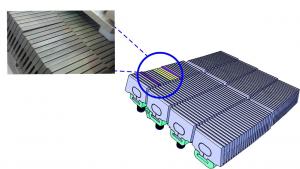

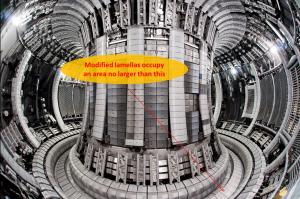

The ITER full-W divertor design goes to great lengths to make sure that there is no possibility—on any of the many thousands of high heat flux handling elements—of an edge sticking up (for example, as a result of mechanical misalignment) that could overheat and begin to melt under the relentless bombardment these components receive during high power operation. However ITER's size means that it will have the capacity to reach a value of stored energy in the plasma more than a factor of 10 higher than the largest currently operating tokamak, JET (EU). When some of this energy is released in a rapid burst (for example due to very transient magnetohydrodynamic events such as ELMs), some melting is possible—even if all edges have been hidden by clever design.

We intend to stop this happening as much as possible by applying ELM control techniques, but occasional larger events cannot always be excluded. So one of the big physics questions we have tried to answer over the past two years is: what exactly happens when a burst of energy, sufficient to melt tungsten, strikes our divertor targets?

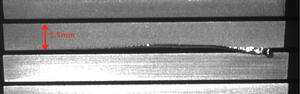

The result: reassuringly unsurprising! Although there was some evidence suggesting the occasional ejection of very small droplets from the melted area, there was very little impact on the confined plasma. As the ELM plasma bursts repetitively melted the edge of the misaligned lamella, the molten material continuously migrated away from the heat deposition zone, accumulating harmlessly into a small mass of re-solidified tungsten. The JET plasmas with 3 MA of plasma current were able to produce ELM plasma pulses very similar to the lowest amplitude events we need to guarantee for 15 MA operation in ITER—a fact which makes the experiments very relevant from a plasma physics point of view.