ITER gyrotrons push technology to the limit

Now, if you want to name a device based on the rotating motion of electrons, gyro and tron come in quite handy. By calling such a device a "gyrotron" you will convey a very clear notion of the principles it is based upon.

In a gyrotron, beams of electrons are accelerated toward a cavity where a strong magnetic field is applied. The interaction between the rotating (cyclotron) motion of the electrons and the magnetic field generate high-frequency radio waves that "travel" in a straight line, almost like an optical beam.

Gyrotrons are powerful devices that have very few applications: industry uses them as heating tools to process glass, composites and ceramics; in magnetic fusion, they contribute—along with ohmic and neutral beam heating—to bringing plasmas to the temperature necessary for fusion.

Gyrotrons are, essentially, energy-delivery devices.

"The area of the plasma that is impacted by the beams is rather small," explains Caroline Darbos, an engineer with the ECRH team, "but the energy spreads fast and evenly. The beams accelerate the electrons in the plasma, which, while generating current, communicate their newly acquired energy to the ions."

"Progress is constant," says Darbos "but we are all working at the limits of technology. We have no experience in steady-state gyrotron operations: the DIII-D tokamak operated by General Atomics in San Diego has experience with high frequency pulses of a couple of seconds only, and the Wendelstein 7-X Stellarator, which will implement 10MW of steady-state gyrotron power, is not yet operational."

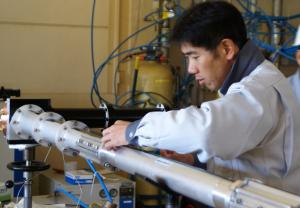

The difficulties are real and there is still a long way to go between prototypes and serial production. However in Lausanne, Karlsruhe, Moscow, Nijni-Novgorod, Naka and soon in Ahmedabad, prototypes are being fine-tuned and test beds readied.