A day in the life of Baptiste, CAD designer

22 Jul 2011

-

Robert Arnoux

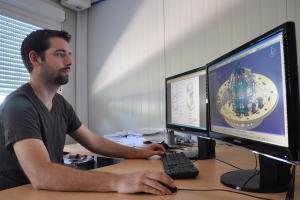

Four years into the job, thirty-year-old Baptiste Martin is a veteran among the 120 CAD designers who work for the ITER Design Office.

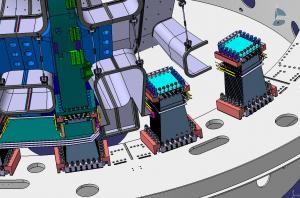

As heavy as a fully loaded Boeing 747, each of ITER's 18 toroidal field coils will rest on a gravity support that is bolted to the machine's pedestal ring. There are 14 "tie rods" per gravity support, and on this Friday morning these small components require Baptiste Martin's full attention.

Thirty-year old Baptiste is a veteran among the 120 CAD (Computer Aided Design), designers who work for the ITER Design Office. Four years into the job, he has acquired an intimate knowledge of the innards of the magnets and the vacuum vessel.

Today's task is to transfer a certain number of design modifications decided by the Assembly Division to the 3D CAD model of the tie rods and "virtually" extend their length several centimetres. The modification will allow room for some cabling destined for the correction coils.

Throughout ITER, dozens of CAD designers are busy working on similar tasks for other components and systems. "A designer produces CAD data based on technical specifications and instructions from the ITER Responsible Officer," explains Eric Martin (no relation to Baptiste), head of the ITER Design Office. "A designer's job is to design or modify an object within the context of its environment. And of course, the environment always affects the design."

3D models, stored and managed in a large database called ENOVIA, form the basis of the ITER design. They allow the designer to visualize the components at any scale and from any angle. The 3D model alone, however, cannot act as a manufacturing blueprint.

Fabien Berruyer, Design Coordinator (DECO) of the cooling water system and Eric Martin, Head of the ITER Design Office, look on as CAD designer Andreea Rîşnoveanu is busy working on a component.

Once a new component—or an update or modification—has been designed and approved, a few supporting "drawings" are necessary to allow the Domestic Agency and its industrial suppliers to turn the virtual object into a physical one by developing a full set of detailed manufacturing data.

How detailed the CAD data transferred by the ITER Organization will be, depends on the category that the Procurement Agreement package falls into: Build-to-print, detailed design, and functional specifications each carry different requirements.

Although an individual designer bent over the computer screen evokes the image of a lonely monk painstakingly drawing letters and illuminations on the parchment of a sacred book, Design Office work is, in essence, team work. As Baptiste modifies the CAD model of the tie rods, he needs to be in close contact with colleagues working on the components that interface with these rods. As do all the other Baptistes working on the other ten million parts of the ITER machine...

Design work at ITER is exceptionally challenging. "Other industries such as aeronautics also build complex machines with contributions from different partners," explains Eric. "But they do so on the basis of a geographical work breakdown: one partner will manufacture the aircraft wings ... another the engines, and so forth. In ITER, all seven Domestic Agencies can be involved in the production of one single component, which makes things considerably more complicated. One thing we're particularly proud of as a team—and that includes the Domestic Agencies—is that we are able to manage that complexity."

How detailed the CAD data transferred by the ITER Organization will be, depends on the category that the Procurement Agreement package falls into: Build-to-print, detailed design, and functional specifications each carry different requirements.

The present policy at ITER, Eric Martin explains, is to produce drawings that are not as detailed as they used to be in order to "leave more freedom to the Domestic Agencies and their suppliers, and to stimulate their creativity." In times of cost containment, also, producing less detailed drawings also eases the pressure on the Design Office human resources.

Although an individual designer bent over the computer screen evokes the image of a lonely monk painstakingly drawing letters and illuminations on the parchment of a sacred book, Design Office work is, in essence, team work. As Baptiste modifies the CAD model of the tie rods, he needs to be in close contact with colleagues working on the components that interface with these rods. As do all the other Baptistes working on the other ten million parts of the ITER machine...

Design work at ITER is exceptionally challenging. "Other industries such as aeronautics also build complex machines with contributions from different partners," explains Eric. "But they do so on the basis of a geographical work breakdown: one partner will manufacture the aircraft wings ... another the engines, and so forth. In ITER, all seven Domestic Agencies can be involved in the production of one single component, which makes things considerably more complicated. One thing we're particularly proud of as a team—and that includes the Domestic Agencies—is that we are able to manage that complexity."

3D models form the basis of the ITER design. They allow the designer to visualize the components at any scale and from any angle.

An intense effort was undertaken over the past three years to "streamline" design activities here at ITER and those conducted by the seven Domestic Agencies. "What we have now," says Eric, "is a truly integrated tool, a truly global design office. Whether a designer is sitting in an office here or thousands of kilometres away doesn't make much of a difference—both of them can access the same databases, and everyone can see what everyone else is doing. Of course, the technology needs to be supported by a human collaborative approach."

Design completion is a top priority for everyone inside the Design Office. But the demands of schedule and those of quality are sometimes conflicting—this is what Eric calls "the designer's dilemma."