Twisting and turning

As part of ITER's in-vessel coil system, two vertical stability (VS) coils will provide fast control of the vertical displacement of the plasma.

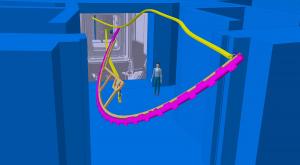

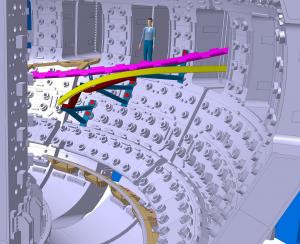

Easing the bulky coils into the vacuum vessel through small openings will be no easy task. Specially designed rails and handling fixtures will have to be installed to guide the bulky coils on their roller coaster ride through the port cell and the vacuum vessel port to their final destination. "I would liken the job to moving a couch into a new apartment—twisting, turning and rotating it as you climb up three flights of stairs and through several narrow hallways and a few really narrow doorways," says ITER mechanical engineer Ed Daly.

That is why the ITER in-vessel coil, assembly, and integration engineers meet regularly these days in the small 3D theatre next to the Tore Supra Tokamak, where CEA/IRFM has set up a virtual reality room. With the help of advanced 3D technology and simulations prepared by CEA in the framework of a contract with the ITER Organization, the engineers can study the movement of the VS coil segments along their integration trajectory and identify potential clashes.