Taking the Big Leap

Thinking back on the potential and the challenges of the endeavour, Rich Hawryluk comments: "The machine we were about to design and build was an incredible extrapolation, arguably even greater than the one we are presently facing with ITER."

It took six years (1976-1982) to build the Tokamak Test Fusion Reactor (TFTR) at PPPL and about the same time (1978—1983) to complete Europe's Joint European Torus (JET) in Culham, near Oxford (UK). In Japan, the boldly named "Breakeven Plasma Test Facility" (later renamed JT-60) began operations in 1985, three years before the Soviet T-15 obtained first plasma. Among these four machines of comparable size, only TFTR and JET were designed to perform deuterium-tritium (DT) operations.

The Columbuses and Magellans of fusion competed as much as they collaborated. "Sure, as you would expect, there was competition," acknowledges Hawryluk, "but it was based on respect for each other."

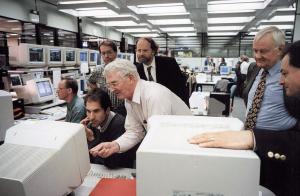

JET and TFTR routinely exchanged data and feedback. "We kept no secrets from each other. However cultures, philosophies and technical approaches were different," says Jacquinot. "More than anything, what each team brought to the other was a different and stimulating intellectual environment."

JET was first to achieve fusion power on Saturday, 9 November 1991. "Today's experiment," read the official press release, "was the first occasion in which the correct fusion fuels, deuterium and tritium, have been used in any magnetic confinement fusion experiment." Close to 2 MW of fusion power had been obtained in a two-second pulse. "This demonstration," continued the press release, "fully confirms that [...] we will be able to design the experimental fusion reactor ITER."

The "friendly competition" was not over. In 1997, JET launched a campaign of what Jacquinot calls "actual DT plasmas" whose most spectacular achievement was not the one that is most often mentioned. "The 16 MW shot of 1997 was spectacular indeed, however we did it mainly to beat TFTR's 1994 results. What really mattered in the 1997 campaign were the 5-second 4 MW stationary shots we did in H mode, because these shots are the basis for extrapolation to ITER."

Hawryluk remembers, "We took it apart as part of decommissioning and examined it. After 15 years of intense operation at and above design requirements, everything still looked very good."

The European tokamak, upgraded with a new divertor, now pursues what remains as its principal mission: being a test bench for ITER, particularly in the realm of ELMs, plasma disruptions and—thanks to a new ITER-like wall—plasma-surface interactions. A year and a half ago, JET Director Francesco Romanelli confided to Newsline that "a deuterium-tritium experiment is envisaged to allow extrapolation of the scenarios to ITER-relevant conditions."