Tore Supra 46,551 shots later

10 Dec 2010

-

Robert Arnoux

After 46,551 plasma shots, the atmosphere in Tore Supra's control room is still one of slight tension, expectation and apprehension.

The lights are dim in Tore Supra's Control Room and the conversations subdued. A plasma shot is imminent and, while the operation has become routine for this 22-year-old machine, the atmosphere in the room is still one of slight tension, expectation and apprehension.

A figure on a small digital panel reads 46,551—this is the number of shots that have been fired since Tore Supra saw First Plasma during the night of 30 March to 1 April 1988. By the end of the work day, the figure will have changed to somewhere around 46,580. Thirty shots is a daily average for an experiment campaign like the one ongoing.

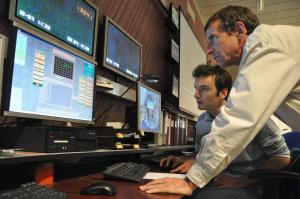

Today's "pilot" is a young engineer, an ELMs-control specialist named Éric Nardon who "learned to drive tokamaks" at MAST, Culham's Mega Ampere Spherical Tokamak. His job is to make sure that all parameters are optimal before pushing the button. Éric works in close coordination with Julien Hillairet and Annika Ekedahl, today's "physicists in charge." As the present three-month campaign is drawing to an end, the Tore Supra team focuses on one objective: "To do the GigaJoule again."

"Pilot" Éric Nardon—here with scientist Patrick Hertout—and the whole Tore Supra team focus on one objective: "To do the GigaJoule again."

In Tore Supra parlance, "the Gigajoule" is the world-record shot of December 2003, unmatched to this day, which lasted six and a half minutes and produced one Gigajoule of energy.

Seven years after this historical shot, Tore Supra is almost a new machine and its operators have considerably more power at their disposal. The tokamak, still the third largest in the world after JET and JT-60U, was recently fitted with new steady-state klystron amplifiers and more powerful heating antennas that make "ITER-relevant" experiments possible.

"We're getting closer everyday. Compared to 2003, we can now produce significantly longer shots and use more hybrid power," says Éric. The present campaign's experiments aim at realizing "the ideal physics configuration" that will enable shots as long as 15 minutes and an energy release of over one Gigajoule.

Tore Supra saw First Plasma during the night of 30 March to 1 April 1988. It was recently fitted with new steady-state klystron amplifiers and more powerful heating antennas that make "ITER-relevant" experiments possible.

The shots also provide for ITER-relevant "side experiments": this morning for instance, a laser beam was used to vaporize part of a small tungsten target into the vacuum vessel and measure the particles' penetration into the plasma. The data collected will contribute to optimizing the ITER divertor which is partly made of tungsten.

What happens inside Tore Supra's vacuum vessel, however, is very different from what will happen in ITER's: the CEA-Euratom machine was not designed to realize deuterium-tritium fusion reactions and no fusion power production was ever expected from its hydrogen, helium or deuterium-only plasmas.

What made Tore Supra unique in its time was its capacity, thanks to a partly superconducting magnet system, to explore the realm of long-duration plasmas. Twenty-two years after it saw First Plasma, its contribution to steady-state operation—and hence to the future of fusion—remains essential.