NSTX-U prepares to re-enter the fusion energy conversation

NSTX-U, the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory's spherical tokamak, is nearing a return to operations. The device will investigate the strengths of the spherical design as a viable route to scalable fusion power plants and test important energetic particle physics for burning plasmas including ITER.

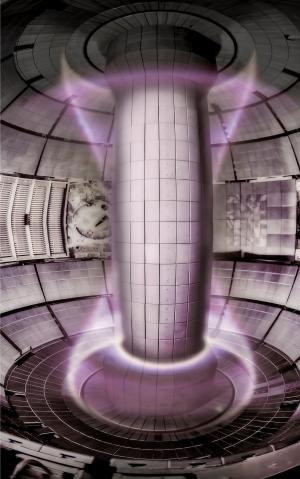

In the wake of these discoveries, fusion research in the late 1980s and 1990s focused on designing tokamaks that could tame this turbulence. Born out of this research was the design of the spherical tokamak, which has a few key magnetic field structural advantages that may allow for increased plasma stability and energy confinement at reactor scale. More compact than traditional tokamaks, these devices have reduced aspect ratios¹, which gives the plasma the shape of a "cored apple" rather than a "donut." This design increases the plasma beta; in other words, the more efficient use of magnetic fields increases plasma pressure to enhance global plasma stability. Other factors—such as subtle changes in magnetic fields, which lead to natural suppression of plasma turbulence, contribute to greater energy confinement capabilities.

That initial NSTX run was paused in 2010 to upgrade the device. NSTX-U was designed to access plasma conditions closer to those expected in future spherical tokamak devices and to test whether the enhanced stability and confinement would extend to these conditions. The upgrades included a new central magnet, which doubled the toroidal field strength from 0.5 Tesla to 1.0 Tesla, doubled the plasma current from 1 to 2 mega amperes, and increased the pulse duration by a factor of five. A second neutral beam injector doubled the heating power and heat flux on the divertor to enable important tests of plasma current sustainment.

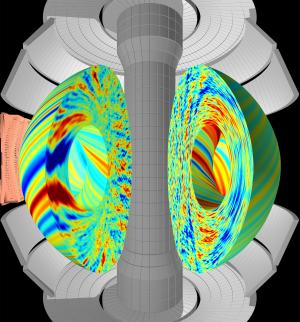

After three years of construction, NSTX-U began operations in 2016, but one of the smaller plasma-shaping magnetic field coils failed after ten weeks of operation. To ensure the reliable operation of all magnetic field coils and other critical components on the device, the NSTX-U Recovery Project has been working to enhance the NSTX-U user facility ever since. Brought in to lead PPPL in 2018, PPPL Director Steven Cowley understands the urgency in getting NSTX-U back online. "People need the data from this machine," he says. Recent progress on the recovery has been steady: the new coils have passed their tests, and operations are scheduled to resume in the autumn of 2025. In the meantime, the PPPL team has not been idle. "Over the last five to ten years, the simulations have really caught up. Our team has been using some really brilliant techniques, known as gyrokinetics, to be able to simulate turbulence with some veracity," Cowley explains. "By using data from the original NSTX run, these simulations indicate that a spherical tokamak at reactor scale will have reduced turbulence, and therefore enhanced confinement."

NSTX-U's experimental data may also have profound commercial implications. "In a practical world," Cowley explains, "fusion is not just about turbulence and confinement." The reduced size of a spherical tokamak may de-risk investment in initial reactors, due to a lower weighted cost of capital. The compact nature of the device is also a long-term advantage. "When you're developing a new technology, you want lots of steps to optimize. With a smaller reactor, you ultimately bring construction costs down by learningas you make lots of them. Just like cars, when you make thousands of them, you develop processes to drive down costs. Engineering doesn't work very well if you only make a few." Of course, reduced size does come with tradeoffs. A smaller aspect ratio may allow for increased confinement, but it also increases the neutron flux on the surrounding materials. Below a certain critical size, a fusion device becomes too small to properly shield superconducting magnets, which Cowley freely admits. "The spherical tokamak pushes up against that limit. Shielding the superconductors, especially in the center of the device, is a challenge." Ultimately, whether these potential benefits are borne out will depend on the results of the NSTX-U campaign.

The data generated from NSTX-U will be a key step in determining the ideal aspect ratio of future commercial reactors. Cowley does not profess to know exactly what that number is. Instead, NSTX-U will contribute to the iterative process of optimizing the design of future fusion power plants. "The idea that we design a fusion reactor, and it stays the same for the next 30 million years, is ridiculous," Cowley explains. "We're going to learn as we go."

Related: See this recent story about NSTX-U from PPPL.

¹The aspect ratio of a tokamak is defined as the major radius (the distance between the centre of the tokamak device and the centre of the plasma) divided by the minor radius (the distance between the centre of the plasma and the edge of the plasma chamber).