Shake, rattle and roll

The ITER Tokamak Complex will rest on about 500 seismic pads that will isolate it from ground motion in the case of an earthquake.

A similar system is being installed at Réacteur Jules-Horowitz (RJH)—the research reactor that is presently under construction at CEA-Cadarache.

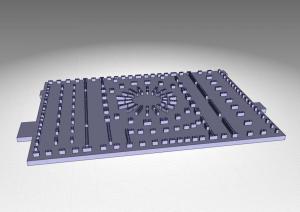

Seismic pads are twenty centimetre-thick "sandwiches" made of six alternate layers of rubber and metal plate. Placed atop concrete columns that rise 2.2 metres from the lower raft of the structure (the groundmat), these 90 by 90 centimetre pads support the upper raft (the basemat) that is the actual "floor" of the installation.

Each of RJH's 195 pads will each bear a weight of 550 tonnes ... and could bear considerably more. The pads are arranged in such a way that the 110,000 tonnes of the installation are uniformly distributed. The same principle will be applied to ITER, where the facility's 350,000 tonnes will be distributed over approximately 600 pads.

Seismic pads are the key to what engineers call "aseismic base isolation." Their flexible structure filters the frequency of the shake, rattle and roll—or more appropriately, the accelerations—that a hypothetical earthquake would cause. "The system is simple, robust and requires little maintenance," says Lionel Germane, a civil engineer at RJH. "It can reduce a potential acceleration of 0.70 G to a mere 0.13 G."

In order to ascertain whether seismic pads can retain their quality and characteristics throughout the installations' lifetimes, a joint qualification program was implemented by ITER and RJH in 2005. "The buildings' mechanical properties rely necessarily on those of the seismic pads," explains Laurent Patisson who managed the qualification program on CEA side before joining ITER as Nuclear Building Section Leader. "It is therefore extremely important to know their variability over time and to integrate this data into the building design."

Seismic pads do age—but slowly. Accelerated aging tests and various mechanical "torture" show that they lose 20 to 25 percent of their flexibility after 75 years, which is longer than the planned lifespan of both installations, including final shutdown and dismantling phases. "In any case," says Lionel, "we must be able to replace any pad if need arises."

In both RJH and ITER, the seismic pad system is sized to withstand an earthquake whose hypothetical intensity is based on data from historical and geological seismic events.

Parameters from the 1708 Manosque earthquake, from the 1909 Lambesc earthquake, and from a "paleo-earthquake" that occurred in the Middle Durance Valley some 9,000 to 26,000 years ago have been computed and their intensity increased to define a "maximum historically-plausible" seismic event.

It is against that ghost of an earthquake that the standing army of pads will protect both installations.