A control room today, whether for a railway system, space mission or power plant, is more than just seats, desks and computer screens. It is a highly organized working environment where nothing is left to chance.

Over the past decades, a branch of science and engineering has developed that aims at optimizing the relationship between the human operators and the systems they operate. "Human factors" is a multidisciplinary approach that incorporates contributions from ergonomics, psychology, ethnography, industrial design, and biomechanics.

It is at the heart of how ITER approaches the design of its Control Room. But what is standard procedure in most industries takes on a special dimension here: the specificity of the ITER experimental machine and operation program generates some unique challenges.

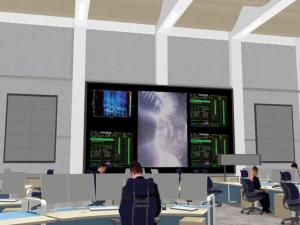

"Due to the complexity of the machine and to the number of people involved both on location and through remote participation, the ITER Control Room is larger than usual," explains ITER head of the Assembly & Operation Division Ken Blackler. "Where JET or Tore Supra have an average of 20 operators in their respective Control Rooms, we will have 60 to 80 operators, engineers and researchers."

The size of the room and the number of operators means that special attention must be paid to noise dampening, seating design, and the floor plan. "The operation of a fusion research device is very collaborative, especially on an international project such as ITER," adds Ken. "You have to anticipate how people will group, and decide on the optimal distance between desks: not too close to prevent a feeling of crammed place ... not too far to facilitate communication."