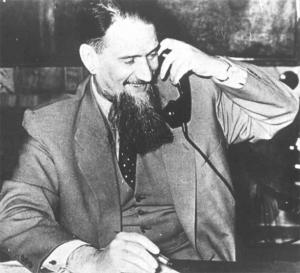

Igor Kurchatov (1903-1960) had been running the Soviet nuclear program since 1943. Now that the USSR was on an equal strategic footing with the US, "The Beard," as he was known to his colleagues at the Laboratory of Measuring Apparatus of Academy of Science (in fact, the Institute for Atomic Research) could now focus his remarkable energy on another quest, maybe the most promising but also the most difficult of all: "the thermonuclear synthesis problem" —in other words, the harnessing of thermonuclear energy for peaceful uses.

And with the blessing of his political patrons "The Beard" was ready to share his results, doubts, and expectations with his colleagues from the West.

It is hard to imagine, from a distance of 60 years, the impact and echo of Igor Kurchatov's conference at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment in Harwell, Oxfordshire — the Holy of Holies of Britain's nuclear research.

"In one bold stroke," writes Robin Herman in

Fusion, The Search for Endless Energy (2), "the Soviet Union overturned the rules of the Cold War information game. Kurchatov laid bare the fact that for the past six years his nation had been conducting research in controlled fusion." Soberly titled "

The possibility of producing thermonuclear reactions in a gaseous discharge," his address was a watershed moment in the young history of fusion research.

Not that it contained any revelation. The 300 Harwell physicists who attended the conference discovered that Soviet scientists "had been following very similar lines of research into magnetic confinement as the UK and the US," write Gary McCracken and Peter Stott in Fusion the Energy of the Universe.

Like their American and European counterparts, the Soviets had developed straight and toroidal pinch experiments, observed neutron emissions and short spurts of hard X-rays in deuterium plasmas, and acknowledged that quite a number of facts "remained to be explained."

Backed by equations, diagrams and high-speed photographs of plasma discharges, Kurchatov's speech did not contain an explicit call for international collaboration. But in shedding light on methodology and experimental results it challenged scientists in the West to reciprocate.

While scientists on both sides were eager to collaborate, many in Western government circles were reticent, especially in the US where it was felt that the Soviet opening was a ruse—a trick to lure politically naïve physicists into giving away precious state secrets.