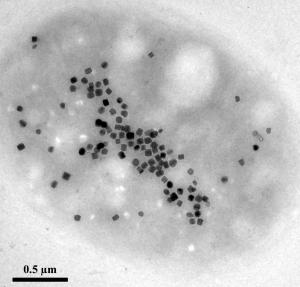

What is new, and what triggered several reports in science magazines throughout the world, is a double breakthrough: first, the identification of a new family of MTB that produces a different—and possibly more promising—type of nanomagnet for biotechnological applications (an iron sulphate named greigite); and second and even more important, the mastering of cultivation that could lead to mass production of MTB.

The excitement was justified. "With MTB, we have an object whose biological activity can be oriented by magnetic fields," explain David Pignol, head of Cadarache's Cell Bioenergetics Laboratory and Christopher Lefèvre, the post-doc researcher who discovered the greigite-producing bacteria and developed the cultivation method.

"We can imagine tweaking their DNA and transferring an extra biological function to their genome, such as the capacity to degrade pesticides or other toxic molecules. Then, we'll have the ability to guide this added biological function with a simple magnet."

The achievement was part of a larger quest that also involved Pr. Dennis Bazylinski at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas; researchers from the French Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS); several universities in France, the US, Brazil and Hungary; and a group of scientists from the Ames Laboratory of the US Department of Energy.

Greigite-producing bacteria, which Christopher Lefèvre isolated in the brackish waters of Badwater Basin on the edge of Death Valley National Park (USA), could open the way to a wide field of application.

Genetically-modified MTB could be used for environmental clean-up or as intelligent contrasting agents in medical imaging techniques such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

NeuroSpin, a CEA research centre on neuroimaging, has begun exploring this technique on lab rodents and will soon extend it to monkeys. Cancer therapy is another potential application, by way of a technique called hyperthermia in which heated crystals could be directed to burn cancer cells.